Archive for February, 2018

Cultivating Mid Career Leaders

Michael Malone’s op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, highlights an avenue for sustained team success.

The hiring process is critical to building a successful strong team.

Our Team Strength tools help companies maintain the focus on developing the most successful teams. When there is a need for an infusion of talent we use a Team approach in the selection process for those new employees.

By enlisting the help of existing team members, we efficiently identify qualified candidates while also determining their values and fit to the culture of the organization. As a result, in 60% of our engagements our clients have identified and hired two candidates for each available position.

The continued strength of a team depends on communication and leadership.

Here’s some highlights from the article that you may find useful to building your Team Strength.

ILLUSTRATION: ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES

The Secret to Midcareer Success

By

Michael S. Malone

Feb. 11, 2018 2:38 p.m. ET

Star employees can rise only so far unless they develop social, or ‘secondary,’ skills.

Why are some top professionals able to maintain peak performance throughout long careers, while others who may be even more talented quickly fade and fall behind? And why do some lesser performers suddenly take off in midcareer and accomplish astonishing things? Two successful tech leaders offer remarkably similar answers to these questions.

Anil Singhal was born in India but emigrated to the U.S. before co-founding NetScout Systems in 1984. Based in Massachusetts, NetScout helps companies and government agencies manage their information-technology networks. A key part of Mr. Singhal’s management strategy has involved helping top young employees make the transition to midcareer success. In particular, he believes that employees’ “primary skills” can take them only so far.

“Those talents by which you earned your college degrees and first made your professional reputation,” writes Mr. Singhal in his upcoming book, can drive success for the first 10 years of a career. After that, “secondary skills”—social qualities like the ability to interact well with colleagues—become the key to continued success.

Mr. Singhal believes that most employers mistakenly nurture primary skills at the expense of secondary ones. This is especially true for employees who are highly productive right off the bat. Unless they move into management or mentorship roles, these increasingly expensive employees can become a drag on employers as their productivity naturally falls off.

That’s where leadership comes in. Facing a career plateau is hard, especially for star employees. But developing the ability to lead creates an avenue for sustained success.

Link to article:The Secret to Midcareer Success

Are you building Team Strength?

We Leverage the insights of the DISC profile with a web-based tool to conveniently identify and address the specific obstacles to teamwork and better results.

- Strategize difficult conversations.

- Coach employees to effectively communicate with each other.

- Maximize your team dynamics.

Get started now on your Team Strength- call 772-210-4499 or email for more information or to set up and an account.

Your Last Five Years: Why Starting Your Exit Planning is Critical with Only Five Years Left

Imagine a doctor has just advised a patient that he must lose twenty pounds – or his life is in danger. If the doctor said the weight loss must happen within one week, that would be a crisis. If the doctor said the patient must lose the weight within one year, it would take some work, but losing twenty pounds in one year would likely not be a crisis for most people.

In that situation, the key issue is time. The amount of time available to lose the weight determines if it’s a crisis, or a reasonable objective. This means that somewhere between one week and one year is a tipping point, where insufficient time creates a crisis, but sufficient time allows for an achievable goal.

The same is true for planning one’s exit. If a business owner for some reason decided he or she wanted to exit but only had one week to get the job done, that would be a crisis. What if that same business owner allocated not one week but rather one decade to plan for exit? Most people would agree that one decade would be sufficient time to achieve a successful exit. So, between one week and one decade, there is a tipping point. How much time is enough to plan one’s exit properly? Is one year sufficient? How about two years? Three? Five? More than five years?

In our experience, that tipping point occurs at five years prior to exit. Meaning, owners who start seriously planning their exit less than five years before the desired date often find themselves without sufficient time to accomplish all of their exit goals, and/or experience greatly increased cost, risk, and stress. Conversely, owners who start their exit planning five years or more prior to exit are more likely to achieve their goals, at lower cost and with less risk and stress.

Why is five years the tipping point?

Listed below are steps that many businesses and their owners need to take to prepare the company and/or themselves for exit. You will note that most of these items can take several years to accomplish—and that’s only if you get it right the first time. For example, if you need to upgrade your leadership team as part of getting the company ready for sale, one wrong hire can easily set you back a year or longer. Review the list below, and you may recognize a project that you might need to get done to prepare for exit, while you’re still leading and growing your business.

All of the following can take up to five years to accomplish:

Identify, hire, onboard, and align a winning leadership team

Reduce owner dependency down to tolerable levels

Achieve compelling performance against multi-year growth plans

Achieve a multi-year run of strong financial results

Outgrow any customer/client concentration

Build a valuable brand protected in a defensible IP portfolio

Time market conditions to your advantage

Evaluate and implement tax-saving strategies

Realize an ROI on employee incentive plans

Address any co-owner exit misalignment

Design and implement ownership and leadership transfer plans (if exiting to key employees or family)

Any one of these projects can take dozens to perhaps hundreds of hours to fully execute. Yet you and your leadership team still need to keep growing your company, because one of the worst things that can happen is your business fails to grow in the final years before you exit.

So, if you’re saying to yourself that you have about five years before you want to exit – you have reached a tipping point. Every day from here gives you less time to achieve your exit goals. Today is the time to get started to avoid that crisis.

Call 772-210-4499 or email Tim to find out more about exit planning solutions.

Ask about our complimentary proprietary tools and checklists. All inquiries are confidential.

The Good, the Bad, and the Unexpected

Exit Planning Webinar:

The Good, the Bad, and the Unexpected:

Lessons Learned Exiting from My Business

Feb 27, 2018 @ 2PM – 3PM EST

Webinar Presenter:

Enjoy a conversation with Doug Calahan, recognized as a Top 25 Entrepreneur of the Year by Business to Business Magazine, and get a real, honest look at what it is like to sell your business.

Doug will tell us all the things that he wishes he had done differently (as well as some of the things that he thought he did well).

This webinar explains how, and covers:

- How he could (should) have made 50% more on the sale of his company

- What the stress of selling a company looks like

- Actions you can begin taking now even if you are not selling for five years

Check out our archive of all past NAVIX exit planning webinars:

Click here to view now

12 Timely Questions the New Tax Laws Raise for Every Business Owner in America

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is perhaps the most sweeping US tax law change in several decades, with a long list of changes to corporate tax rates, personal income tax rates, and other areas. The new laws change much of the tax landscape for businesses and their owners—now and at exit.

Therefore, owners contemplating exit should sit down with their tax, legal, financial, and exit advisors to discuss the new laws and evaluate what steps they must take in this new world.

To aid you, listed below are 12 questions that owners should put to their advisors. We recommend owners print this list and set up a meeting with their advisory team to discuss and review:

12 Questions that Owners Should Put to Their Advisors

Under the new laws, which legal form(g., C-corporation, S-corporation, LLC, partnership, etc.) is most advantageous for our current needs? How about at exit?

Which of themany new and revised tax regulations under TCJAmay NEGATIVELY impact our business? What actions should we consider as a result?

Which of the many new and revised tax regulations under TCJA may POSITIVELY impact our business? What actions should we consider as a result?

Does TCJA contain any provisions that require us to re-evaluate our current: ownership structure, owner compensation practices, capital structure, and equipment purchasing and/or leasing plans?

Given that our likely exit strategy is to one day (Pick one):

□ Sell to an outside buyer

□ Sell to an inside buyer

□ Pass the business down to family

□ Shut the business down

Under the new tax laws, we should:

_______________________________________

(Answer with the actionable ideas discussed with your advisor)

Given that our desired exit timeframe is to exit (Pick one):

□ Within next 12 months

□ Between one and three years from now

□ Between three and five years from now

□ Between five and ten years from now

□ Longer than ten years from now

Under the new tax laws, we should: _________________________________________

(Answer with the actionable ideas discussed with your advisor)

What will my personal income tax picture look like under the new laws? (We recommend modeling them to compare before and after TCJA.)

If the new laws present a significant change (positive or negative) to my personal income tax burden, consequently, what steps should I consider to best achieve my immediate and future financial goals?

Which of the many new and revised tax regulations under TCJA may negatively impact my personal financial planning and picture? What actions should we consider as a result?

Which of the many new and revised tax regulations under TCJA may positively impact my personal financial planning and picture? What actions should we consider as a result?

What changes, if any, should I consider to my personal estate planning as a result of the new tax laws?

What else should I consider doing within my business and my personal financial affairs as a result of the new tax laws that we have not yet discussed?

We encourage you to review these questions with your trusted advisors as soon as possible.

If you would like to review your answers with a NAVIX Consultant, Call 772-210-4499 or email Tim for a complimentary 45-minute consultation.

12 questions that Owners Should Put to Their Advisors

Is your company built for long term success?

Each month I share a favorite book review from Readitfor.me.

There is never enough time to read all the latest books – this tool is a great way to learn and to stay on top of the latest topics and new ideas.

If you are like my clients, you work hard learning how to grow your company or organization. You invest the time and money to improve your team for better results and increased value.

How can you build your company for long term success?

Read on…

Built To Last

by Jim Collins

Some companies are built to be very successful for a very long time. Jim Collins and Jerry Porras teach us how to do it.

In Built To Last, Jim Collins and Jerry Porras research and explain the characteristics of companies that have massive success over a long period of time.

These companies are:

- Premier institutions in their industry

- Widely admired by knowledgable businesspeople

- Made an significant impact in the world

- Had multiple generations of CEOs

- Been through multiple product (or service) life cycles

- Were founded before 1950

How do we know that these companies are so valuable? They compared these visionary companies with a comparison company that were founded at a similar time and in a similar industry. Think Ford vs GM, or HP vs Texas Instruments. In other words, other solid companies that were better than the general market.

They found that $1 invested in the comparison companies would have returned two times what the general market would have returned. But the visionary companies would have returned fifteen times the general market.

In essence, these companies have something to teach us about what it takes to be very good, for a very long time.

How did they do it? Let’s find out.

Clock Building, Not Time Telling

The authors use the metaphor of building a clock versus telling the time to make the first important distinction between the visionary companies and the comparison companies.

When you are merely telling the time, you are focussed on having a great idea or being a charismatic company leader.

Instead, a clock builder focusses on building a great company that can thrive beyond any product cycle or leader.

Interestingly, few of the great companies in their study can trace their roots back to a great idea or excellent initial product. Some of them began as outright failures.

When Masaru Ibuka founded Sony in 1945, he had no initial product idea. After considering bean-paste soup and miniature golf equipment as two potential first products, they settled on their first product – a rice cooker. It’s first significant product – a tape recorder – failed in the marketplace.

For the visionary companies, a runaway hit product was never the ultimate goal. Creating an enduring company was. As the authors describe it, the shift was in seeing the products as a vehicle to create the company instead of the company as a vehicle to create products.

The builders of the visionary companies were ready to kill or revise a failing product, but were never willing to give up on the company.

Something very interesting happens when you focus on creating an enduring company instead of great products – you realize that you don’t need a high-profile charismatic leader to succeed.

“Tyranny of the OR”

Another interesting thing the authors found was that the visionary companies didn’t seem to make the trade-offs that most companies would make.

Where most companies would make a choice – you can have change OR stability, or low cost OR high quality – the visionary companies would find ways to have both at the same time.

More Than Profits

Visionary companies exist to do more than just make money, where the comparison companies typically don’t.

If you go to business school they’ll teach you that the core purpose of a company is to make money for it’s shareholders. Making money is obviously necessary for a company to survive. Only in Silicon Valley can companies go on for years burning through mountains of cash and still stay in business.

But the visionary companies don’t put profit first – their put their hopes and dreams for what the company can do beyond creating a profit first.

This is what the authors call the core ideology of the company. It is a set of basic precepts that say this is who we are, this is what we stand for, and this is what we are all about.

The core ideology is a combination of core values and purpose.

The core values of a company are the essential and enduring principles that drive all decision making at the company. The Johnson and Johnson Credo is an often cited example (go look it up if you have some time). They remain fixed over time, the bedrock on which the entire company is built.

The purpose of a company is the set of fundamental reasons for the company’s existence beyond just making money. The purpose should be broad, fundamental and enduring. It is something to continuously pursue, not to achieve.

As Walt Disney once said:

Disneyland will never be completed, as long as there is imagination left in the world.

Preserve the Core/Stimulate Progress

Thomas J. Watson, Jr., the son of IBM’s founder and the 2nd president of the company, sums up what the authors are getting at in this section of the book when we says:

“If an organization is to meet the challenges of a changing world, it must be prepared to change everything about itself except its basic beliefs as it moves through corporate life…The only sacred cow in an organization should be its basic philosophy of doing business.”

Preserving the core while stimulating progress is the central concept of this book.

Stimulating progress in the visionary companies is an internal drive, not an external one. They don’t wait for the market to tell them it’s time to improve. They feel compelled to do it on their own – like a great artist feels compelled to create.

The trick is to have a firm understanding of what your core actually is. Most companies in the comparison group mistake strategies and tactics for their core, and thus don’t change their strategies and tactics readily enough.

Unfortunately, that also allows them to drift from their core purpose, leading to the double whammy of a rudderless company fixated on tactics and strategies that will eventually stop working.

Now that we’ve got the core idea of the book nailed down, it’s time to move onto the five categories of preserving the core and stimulating progress you can use to become a visionary company.

Big Hairy Audacious Goals (BHAGs)

Although I have a natural fear of things that are big and hairy, I’m willing to make an exception here.

BHAGs are commitments to challenging and often risky goals toward which a visionary company channels its efforts.

It’s the difference between having a good old regular goal, to becoming committed to a huge and daunting challenge. The most often quoted BHAG of all-time is when Kennedy told the world the US would land a man on the moon before the end of the 1960s were up.

In order to work, the BHAG needs to be clear and compelling. Your people need to “get it” right away – it should take little or no explanation.

GEs goal in the 1980s fit the bill. Their goal was to “Become #1 or #2 in every market we serve and revolutionize this company to have the speed and agility of a small enterprise.”

When you read your BHAG, there should be some part of you that tells you that you’ve set yourself an unreasonable goal. But there should be another part of you that tells you that you can do it anyways.

People outside your organization will think (and sometimes tell you right to your face) that you are crazy.

But when you set it right, it will galvanize the energy of your entire company towards achieving it.

Cult-like Cultures

The visionary companies build a culture that is a great place to work only for those who buy in to the core ideology. Those who don’t fit in with it are ejected like a virus, which helps to preserve the core.

That’s because when you are very clear about what you stand for, and very clear about where you are heading (someplace amazing and scary at the same time), you tend to be more demanding of your people.

This causes some people to compare these types of companies to cults. In fact, as the authors point out, they do share at least four characteristics with them.

- a fervently held ideology

- indoctrination

- tightness of fit

- elitism

When you show up to a visionary company, you are going to be reminded of your purpose and BHAG on a regular basis. You’ll be rewarded in many ways if you become a permanent part of the team. And you’ll feel a sense of elitism because out of all of your friends, you’ll be the only one working on a mission greater than earning a paycheque.

To make the comparison complete, the people around you will probably accuse you of “drinking the Cool-Aid.”

But that’s ok – that’s what it takes to become a visionary company.

One last point on this topic – this is NOT about creating a cult of personality – this is about creating a cult of purpose and mission.

Try a Lot of Stuff and Keep What Works

To me, this sounds an awful lot like what people today would call the Lean Startup method. Or at least the beginnings of it.

In visionary companies we see high levels of action and experimentation – often planned and undirected – that produce new and unexpected paths of progress that enable visionary companies to mimic the biological evolution of species.

As Richard Carlton, the former CEO of 3M once said:

“Our company has, indeed, stumbled onto some of its new products. But never forget that you can only stumble if you are moving.”

Many of the visionary companies made transitions from one market to another not because of detailed strategic planning, but by experimentation, opportunism, and sometimes by accident.

American Express started off as a freight business in 1850. One of the things they originally shipped was cold hard cash (think of a Brinks truck today and you get the idea). The creation of money orders forced a decline in demand for their cash shipping service, so they created their own money order, which they called the “Express Money Order.” That started their transformation into the financial juggernaut we know today.

Each of the visionary companies exhibited this kind of behaviour. 3M famously created the Post-It note as a failed experiment into a permanent adhesive, which one of their engineers used to mark pages in his church hymnal. The rest, as they say, is history.

If you want to create a culture where evolutionary progress takes hold, start with these five principles.

- Give it a try—and quick!. Try new things, adjust to what you find, and for heaven’s sake, keep moving.

- Accept that mistakes will be made. The nature of experimentation is that you don’t know what you’ll find. So some things will work, and others won’t. Accept that mistakes will be part of the process.

- Take small steps. Small steps serve two purposes. First, any small mistake won’t sink the company. Second, many small steps put together are what it takes to make real progress.

- Give people the room they need. Give your people the latitude to try new things.

- Build the clock. Turn the previous four steps into something that becomes part of your culture.

Home-grown Management

In visionary companies we see a lot more promotion from within the company, which means that the senior management is always filled with people who’ve spend a significant amount of time immersed in the core ideology of the company.

This one is pretty straight-forward and doesn’t require much more explanation.

Just remember that you need to have a management development process and long-term succession planning in place to ensure a smooth transition from one generation to the next.

If you are doing a good job of developing talent internally and keeping them indoctrinated in your core purpose, you should have no problem finding your next great executive from your ranks.

Good Enough Never Is

In the visionary companies, we see a “continual process of relentless self-improvement with the aim of doing better and better, forever into the future.”

The critical question for each of the visionary companies is not “how are we doing compared to our competition?”, it is “how can we do better tomorrow than we did today.”

In fact, visionary companies will go to great lengths to ensure that they create discomfort so that they can create change before the external world demands it.

As an example, in the early 1930s, P&G already had the best products, the best people, and the best marketing. So they designed a brand management structure that allowed P&G brands to compete directly with other P&G brands.

In each of the visionary companies the authors found some sort of discomfort mechanisms to combat complacency – which is something that the best in any field have to combat.

Boeing had a practice they called “eyes of the enemy”, where they assigned managers the tasks of coming up with business plans with the sole purpose of destroying Boeing. Then they would come up with plans to respond to those (imagined, but very real) threats.

The goal for the visionary companies is to ensure the long-term health of the company, which requires constant investment into the future. This includes when times are good, and when times are bad. Long-term health is never sacrificed in the name of short-term profits.

Conclusion

Interestingly, much of what was written about these Built To Last companies is coming back into fashion about 35 years later.

What I want to suggest is that these principles were once required if you wanted to build a great and enduring company. These days, it seems as though you need to follow these principles if you merely want to survive.

Companies with long term success have strong teams.

Our Team Strength tools help companies maintain the focus on developing the most successful teams. When there is a need for an infusion of talent we use a Team approach in the selection process for those new employees.

By enlisting the help of existing team members, we efficiently identify qualified candidates while also determining their values and fit to the culture of the organization. As a result, in 60% of our engagements our clients have identified and hired two candidates for each available position.

Please share this summary with a friend/colleague

Exit Planning Under the New Tax Laws: Should You Be a C-Corporation?

While there are many material differences between C-corporations and other legal forms, for this purpose the most important tax difference is that C-corporations pay taxes on income, whereas the other commonly used legal forms are pass-through entities, which mean taxable income (or losses) “pass-through” to the owners’ personal income tax returns. This difference is relevant because, despite the much-hyped tax cut, owners of C-corporations still face under the new tax laws the risk of double-taxation when they sell the company. If double-taxation sounds bad, that’s because it usually is.

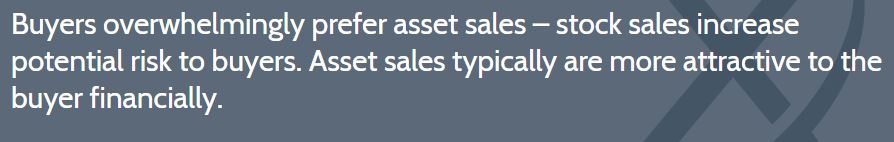

Here’s what double-taxation means, and why it occurs. When corporations are sold, the buyer has a choice to make. Does the buyer want to purchase the corporation’s stock from whomever or whatever owns it, or does the buyer want to purchase the company’s assets from the corporation itself? The two options are thus called stock sales (a.k.a. entity sales) and asset sales. Buyers overwhelmingly prefer asset sales, for two main reasons. First, stock sales increase potential risk to buyers, because if they buy the stock, they may inherit future liabilities attached to that stock, whether known or unknown at the time of sale. The second reason buyers overwhelmingly prefer asset sales is because asset sales typically are more attractive to the buyer financially. In an asset sale, the buyer gets to depreciate on its tax return some assets faster than it commonly would be able with a stock sale. For these two reasons, buyers prefer asset sales.

Are you familiar with the adage that says in any negotiation between two parties where one has all of the money, and the other does not, the one with the money wins? Well, the adage applies here. The buyers have the money. So, more often than not, buyers get their way and require asset sales. (There is even a provision of the tax code called Section 338(h)(10) that lets buyers treat the sale as if it were an asset sale for tax purposes, even though structurally the transaction was a stock sale. This is called a deemed asset sale.)

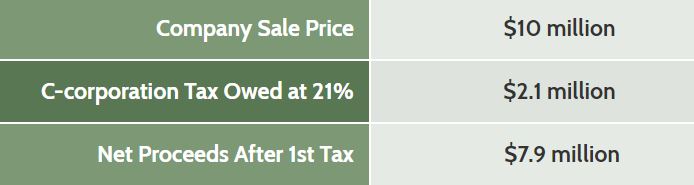

So that means if you intend to sell your company one day, the future sale most likely will be an asset sale. That’s when double-taxation kicks in. First, the buyer purchases from the corporation its assets. At that point, a C-corporation now has to pay any taxes owed from the sale of its assets. Let’s create a simple example. Assume a $10 million asset purchase price, and the company pays exactly 21% in taxes, which is $2.1 million.

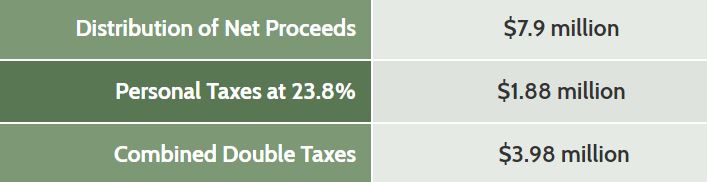

Once the dust has settled, the seller is now left with an empty C-corporation, other than the $7.9 million in after-tax cash from the sale proceeds sitting in the company’s bank account. At that point, the seller wants to take money home thank-you-very-much, and so distributes the money out to the owner(s). That triggers the second tax. Let’s assume that second tax is all long-term capital gains taxes at 20%, plus the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax that usually applies. So now that’s another $1.88 million in personal taxes ($7.9 million X .238) as shown below. Put the two levels of tax together, and the total taxes paid at sale are about $3.98 million on the original $10 million sale.

The double-taxation creates almost a 40% total tax burden—and this example does not include any state or local taxes, which would only add to the total. So, even though the C-corporation tax rate is reduced, if you intend to sell your company one day to an outside buyer, it remains highly disadvantageous to sell your business while a C-corporation in most situations.

One last important point to remember: If you have a company that is a C-corporation that you expect to sell, and to avoid double-taxation you usually would convert that C-corporation into an S-corporation. However, you must outwait that conversion by five years to eliminate all risk of double-taxation at sale. This arcane tax provision is called the Built In Gains tax—yes, the BIG tax. We can’t make this stuff up.

Operating as a C-corporation may only be advantageous if you are confident that you will not sell the company for any reason within the next five years, or if you never intend to sell your business but instead you give it to family members in the future. All of this reinforces that business owners need to think through their exit and plan ahead on tax questions, many years prior to exit.

This information is for educational purposes only. Please consult your tax, legal, and other advisors to evaluate how this material may apply to you and your businesses. NAVIX does not provide tax or legal advice nor services.

Call 772-210-4499 or email Tim to find out more about exit planning solutions.

Call 772-210-4499 or email Tim to find out more about exit planning solutions.

Tim is a Consultant to Business, Government and Not-for-Profits Organizations specializing in innovative and challenging ways for organizations to survive, to thrive and to build their teams.

Tim is a Consultant to Business, Government and Not-for-Profits Organizations specializing in innovative and challenging ways for organizations to survive, to thrive and to build their teams.